A cradle of Nepali civilization, art, culture, religion, and life, the Kathmandu Valley is tucked away between the hills and in the center of the Himalayas. The landscape of Kathmandu Valley often piques people’s interest in its formation and history.

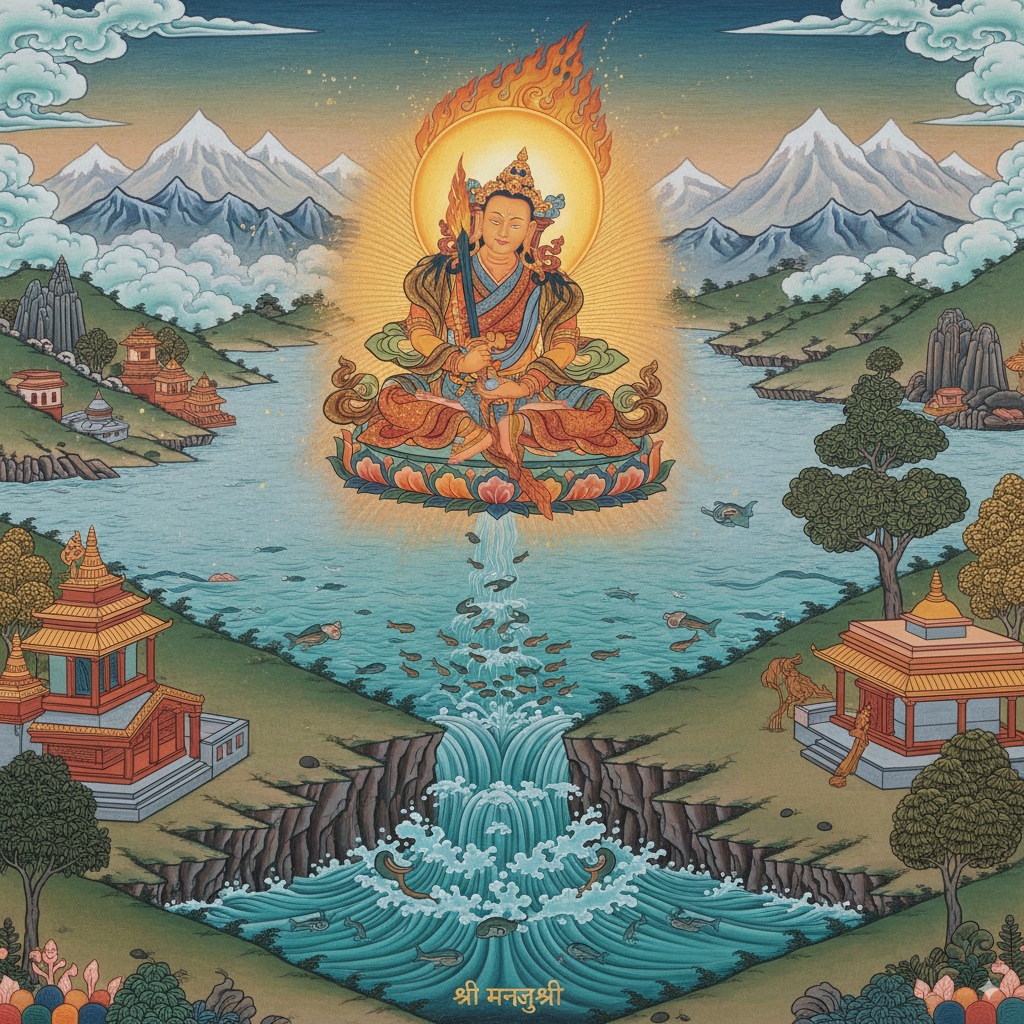

The fascinating tale reveals the ways in which a colossal lake in this valley transformed into an active hub of culture and trade, interwoven with myth, spirituality, and geological transformation in a single slash of a sword.

Using Buddhist texts, Newar oral traditions, and historical sources, this essay investigates the mythology of Manjushri, the rise of Swayambhu, and the significance of these events in the formation of the Kathmandu Valley.

The Sacred Lake and Swayambhu Myth

In the past, the Kathmandu Valley was a huge lake encircled by hills and trees, unaltered by human civilization, according to old Buddhist writings, mythology, and even geology.

The mythology goes on to say that an eternal flame (Swayambhu Jyoti) shone on a magical lotus that bloomed in the midst of this enormous lake, reflecting the purest form of enlightenment.

This incredible flame, which symbolizes the holy presence of Buddha-nature in the world, arose on its own.

For celestial beings, sages, and deities who considered the valley to be a sacred location, the flame lotus was a potent object that was also revered. However, the outside devotees were unable to access the lotus or the holy light due to the overwhelming waters of the lake.

The spiritually rich Kathmandu Valley remained uninhabitable, with its sanctuaries concealed beneath the surface of the lake’s deep waters.

The Swayambhu Purana fascinatingly relates about the legendary Nagarajas, or Serpent Kings, that originally occupied the Kathmandu Valley. Although the name Nagaraja literally means “Serpent King,” it refers to much more than only biological serpents.

They were the protectors of the sacred lake, and the Naga represents a deep-rooted natural energy related to the Earth’s life force, water, and natural phenomena like rainfall. These serpentine creatures are also linked to the prosperity of both humans and animals, as well as the fertility of plants.

Manjushri and the Sword of Wisdom

Manjushri is a bodhisattva in Mahayana Buddhism who represents the prajna (transcendent wisdom) of the Buddhas. The name “manjushri,” which means “Beautiful One with Glory” or “Beautiful One with Auspiciousness,” is a combination of the Sanskrit word “manju” and the honorific “sri.” Manushri can also be known by the full name Mañjuśrīkumārabhūta.

One of the most important and ancient Bodhisattvas in Mahayana Buddhism, Manjushri is cited by Shakyamuni Buddha in a number of his scholarly teachings. Numerous allusions can be found in a number of Buddha-era myths and stories that are still widely recognized today.

The story of Manjushri clearing the Kathmandu Valley in Nepal for human habitation is among the most well-known.

Buddhist texts state that Manjushri spent three nights on a hill east of Kathmandu while journeying through the Himalayas from Mount Wu Tai in China.

And it was here that he saw the bright Swayambhu flame from afar, and he embarked on a voyage to discover the significance of the light, impressed by the sight of such a celestial flame in the midst of the lake.

And as he came closer to the place, he realized its religious significance and resolved to approach the giant lotus while also making it accessible to others.

He carved a gorge at Chobhar to drain water from the lake with a single swipe of his sword. And he transformed the valley physically and spiritually with the swing of his sword of wisdom.

Nonetheless, the Swaymbhu Purana also describes how earlier Buddhas, including Vishwabhu and Krakuchchhanda, saw the Great Lake and predicted the arrival of a wise man named Manjushri, who would empty the valley.

And after emptying the lake in the Kathmandu Valley, Manjushri discovered displaced serpent deities (nāgas) and established Taudaha as a haven for them, especially the Naga King Karkotaka and his family.

This deed emphasizes the bond between people and the spirits of nature as well as the significance of creating safe spaces for all living things.

The lake has many stories and mythologies associated with it. Even though he established the groundwork for a magnificent civilization, not everyone was pleased with Manjushree’s deed. The nearby supernatural beings, mythological spirits, and the hill deity were among those who were upset by his actions.

Emergence of the Swayambhu Stupa

When the lake was drained entirely, the ethereal lotus that had been floating on water settled and transformed into a hill. It was believed that the valley’s spiritual hub was located here.

This hill became a sacred spot where the perpetual flame (Swayambhu Jyoti) burned and continued to shine on this hill.

The term “Swayambhu” means “self-existent” or “self-arisen,” referring to the belief that the flame and stupa appeared naturally, without human intervention.

While the site was revered since ancient times, historical evidence suggests that the Licchavi rulers (around 5th century CE) built or renovated the stupa that survives today.

The stupa is thought to have been constructed over the precise location to further enclose and safeguard the sacred light, establishing a tangible and long-lasting testimony to the divine presence.

For example, the stupa building consists of a 13-tiered spire representing the stages of spiritual accomplishment, a dome, and a square harmika with Buddha’s all-seeing eyes on either side.

Spiritually, the stupa represents the Buddha’s thought and the path to enlightenment; circumambulating it is a devotional exercise that cleanses karma.

Manjushri’s Role in Shaping Civilization

After the great lake was miraculously drained, Manjushri remained in the valley, but his position changed from divine landscaper to civilizing force. The development of the Kathmandu Valley was more than just a physical alteration; it was the deliberate establishment of a new culture.

The Swayambhu Purana states that Manjushri established the first city in the valley, which he called Manjupattana, because he believed that the valley would be the ideal location for civilization.

The lake’s lush soil made the valley perfect for farming, which further facilitated the growth of communities, commerce, and culture.

Manjushri made Dharmakara, a devoted follower, the first king of the Manjupattana in order to guarantee the stability and appropriate administration of this new community.

By appointing him as the ruler, Manjushri created a dynasty of kings and a dharma-based system of government, guaranteeing that the new civilization would flourish under capable leadership.

Furthermore, the entire experience cemented Manjushri’s reputation as the founder of the Kathmandu Valley. He is renowned not only for his act of spiritual insight in draining the lake but also for his practical acumen in constructing a habitable area, erecting a city, and establishing a society with a clearly defined leader.

These and many other devotional acts are traits attributed to Manjushri in the Swayambhu Purana. It further states that Manjushri returned home, made all the necessary arrangements, and shortly after, he became a Bodhisattva by transcending his human body.

Rituals and Festivals at Swayambhu

The Kathmandu Valley as it exists today is the product of centuries of historical and mythical occurrences that have influenced modern celebrations and rituals.

As an act of merit and cleansing, hundreds of thousands of devotees visit the Swayambhu stupa every day to offer prayers and offerings.

Festivals like Tihar (festival of lights) and Buddha Jayanti (birth of the Buddha) are celebrated at Swayambhu with unique ceremonies, drawing pilgrims and tourists and highlighting Nepalese society’s diversity in religion and culture.

During the Nepalese month of Gunla (August/September), the Newari people celebrate the Gunla festival. With offerings and musical processions, the devotees travel to other Buddhist locations, such as Swayambhu.

These customs preserve the story and the spiritual core that unites individuals and fortifies ties within the group.

Conclusion

The Swayambhu stupa and the Manjushri legend serve as powerful symbols of the Kathmandu Valley’s spiritual foundation. This mythology blends religion, mythology, and the natural world to explain the origin of one of Nepal’s holiest locations and a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Beyond the amazing draining of the old lake, the valley’s strong ties to Buddhist teachings and human advancement are reflected in Manjushri’s dual roles as a founder of civilization and a figure of divine wisdom.

Swayambhu is a living example of centuries of religious belief, devotion, and cultural identity in addition to being a marvel of architecture. Communities are still bound together by the customs and festivals observed here, which preserve the history and religion that shaped Kathmandu.

This combination of myth and history evokes awe and reflection while reminding us of the valley’s hallowed past and its ongoing journey into the future.